The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) Section 404 remains one of the most misunderstood areas of public company compliance. Even more than 20 years after SOX was enacted, many CFOs, Controllers, Internal Audit leaders, and SOX Managers still operate under assumptions that create unnecessary audit friction, inflated costs, and avoidable control deficiencies.

This article addresses the most common misconceptions about SOX 404 audits, explains what regulators and auditors actually expect, and provides practical, audit-defensible guidance based on how SOX works in practice—not theory.

As a CPA-level SOX advisor who has supported first-year filers, accelerated filers, IPO-ready companies, and mature SOX programs, I’ll distinguish clearly between requirements, best practices, and commonly accepted approaches, while highlighting where companies most often go wrong.

What SOX 404 Really Requires (Quick Refresher)

At its core, SOX 404 requires management of public companies to:

- Design and implement internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR)

- Evaluate the design and operating effectiveness of those controls

- Conclude on the effectiveness of ICFR as of year-end

External auditors then independently test and opine on ICFR (for companies subject to 404(b)).

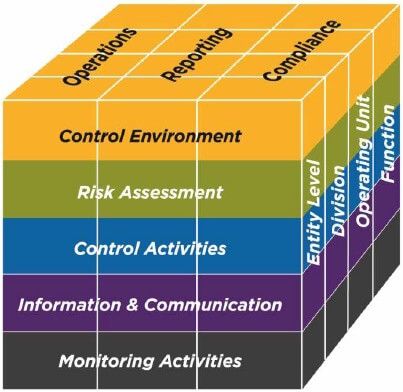

This requirement is grounded in principles issued by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and aligned to the COSO Internal Control – Integrated Framework .

With that foundation, let’s address the misconceptions that cause the most confusion—and risk.

Misconception #1: “SOX 404 Is the Auditor’s Responsibility”

Reality: SOX 404 is management’s responsibility, not the auditor’s.

Why This Misconception Exists

Many companies experience SOX primarily through the lens of external audit requests, testing schedules, and deficiency discussions. Over time, SOX can feel like an “audit-driven” exercise.

What Regulators Actually Expect

Management must:

- Identify financial reporting risks

- Design and implement controls to address those risks

- Execute the controls

- Evaluate design and operating effectiveness

- Document and conclude on ICFR

Auditors:

- Perform independent testing

- Evaluate management’s assessment

- Issue an opinion (for 404(b) filers)

Key Point: Auditors do not design, fix, or “own” your controls. If a control fails, it is a management failure, even if the auditor identified it.

Practical Example

If an auditor identifies a lack of review evidence for a journal entry control, the issue is not “audit documentation”—it is a control execution failure by management.

Misconception #2: “SOX 404 Is Just About Documentation”

Reality: Documentation supports SOX—but controls must actually operate effectively.

Where Companies Go Wrong

Especially in first-year SOX programs, companies often:

- Focus heavily on narratives and flowcharts

- Over-document processes

- Underinvest in control execution discipline

Auditors test what happened, not what was written.

What Auditors Care About

Auditors evaluate:

- Design effectiveness: Does the control, if performed as described, prevent or detect a material misstatement?

- Operating effectiveness: Was the control actually performed, by the right person, at the right time, with sufficient precision?

Common Failure Pattern

“The control is documented, but there’s no evidence it was performed.”

This is one of the most frequent causes of control deficiencies.

Misconception #3: “If It Didn’t Cause an Error, It’s Not a Deficiency”

Reality: SOX deficiencies are assessed based on risk, not just actual misstatements.

How Deficiencies Are Evaluated

Deficiency severity considers:

- Reasonable possibility of a misstatement

- Potential magnitude of the misstatement

- Compensating controls

- Pervasiveness across accounts or processes

Material Weakness vs. Significant Deficiency

- Material weakness: A reasonable possibility that a material misstatement would not be prevented or detected

- Significant deficiency: Less severe but important enough to merit attention

An issue can be a material weakness even if no error occurred.

Why Auditors Care

SOX is preventive. Waiting for an error before addressing a control gap defeats the purpose of ICFR.

Misconception #4: “IT Controls Are an IT Department Problem”

Reality: IT General Controls (ITGCs) are financial reporting controls, owned by management.

Why ITGCs Matter

ITGCs underpin:

- Automated controls

- System-generated reports

- Data integrity used in manual controls

Weak ITGCs can:

- Undermine reliance on automated controls

- Expand substantive audit testing

- Increase SOX costs significantly

Common ITGC Misunderstandings

- “The system is reliable because it’s a well-known ERP”

- “User access reviews are an IT formality”

- “Change management isn’t relevant to financial reporting”

Auditors assess whether ITGCs support ICFR reliance, not IT best practices.

Misconception #5: “SOX 404 Is the Same Every Year”

Reality: SOX is risk-based and dynamic.

Why This Assumption Is Dangerous

Companies that treat SOX as a static checklist often miss:

- New risks from system implementations

- Business changes (acquisitions, restructuring)

- Changes in accounting standards

- Personnel turnover in key control roles

What Should Change Annually

- Risk assessment

- Scoping decisions

- Key controls

- Testing approach

- Management judgment

Auditors expect SOX programs to evolve with the business.

Misconception #6: “Auditors Require All These Controls”

Reality: Management determines which controls are necessary.

The Root Cause

Companies often:

- Add controls “because audit asked for it”

- Over-control low-risk areas

- Create unnecessary review layers

Best Practice

Management should:

- Perform its own ICFR risk assessment

- Identify key controls that address material risks

- Push back (professionally) on non-risk-based control creep

Auditors may challenge management’s conclusions—but they do not dictate control design.

Misconception #7: “First-Year SOX Failures Are Expected”

Reality: First-year challenges are common—but material weaknesses are not inevitable.

First-Year SOX Pitfalls

- Late program kickoff

- Incomplete risk assessment

- Poor documentation discipline

- Unclear control ownership

- Underestimating ITGC effort

First-Year Timeline Reality

Successful first-year filers typically:

- Start SOX planning 9–12 months before year-end

- Perform interim testing

- Remediate before year-end

- Align Internal Audit, Finance, IT, and External Audit early

A failed first-year SOX opinion often reflects planning issues, not business complexity.

Misconception #8: “SOX Is Just a Compliance Exercise”

Reality: When done well, SOX strengthens financial governance.

Strategic Benefits of a Mature SOX Program

- Clear ownership of financial controls

- Better close discipline

- Reduced audit surprises

- Stronger IPO readiness

- Increased Audit Committee confidence

While SOX is mandatory, companies that treat it purely as a checkbox incur higher costs and frustration.

Common “People Also Ask” Questions

Is SOX 404 required for all public companies?

SOX 404(a) applies to all public companies. SOX 404(b) applies to accelerated and large accelerated filers, with exemptions for certain smaller reporting companies.

Can Internal Audit perform SOX testing?

Yes. Internal Audit often performs management’s testing, but management retains responsibility for conclusions.

How often must controls be tested?

Key controls are typically tested annually; some may be tested more frequently depending on risk and reliance strategy.

Executive Summary: What to Get Right

- Management owns ICFR—not auditors

- Documentation supports controls; it doesn’t replace them

- Deficiencies are risk-based, not error-based

- ITGCs are critical to financial reporting

- SOX must evolve with the business

- First-year success depends on early planning